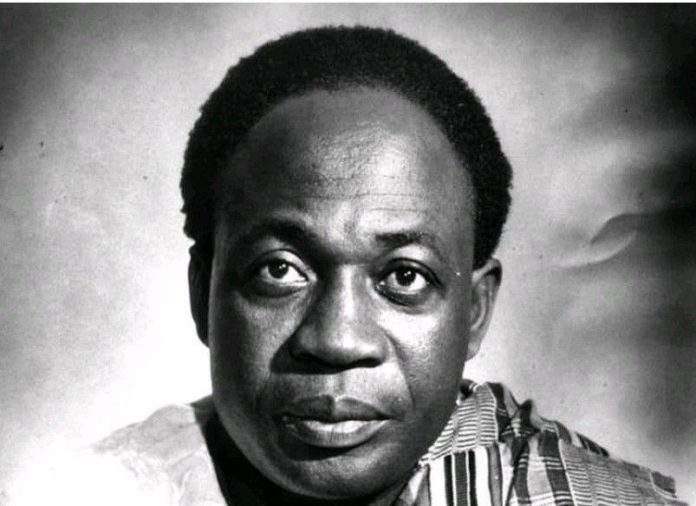

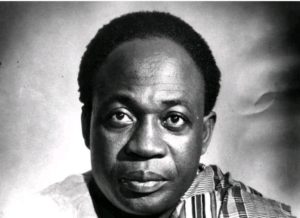

The day is May 3, 1964 and The New York Times carries a scathing headline about a young African country, Ghana: Portrait of Nkrumah as Dictator. It gave a litany of cardinal sins that Kwame Nkrumah, the Ghanaian leader, had committed against democracy and civilization in general. Chief among these sins was that Nkrumah’s political party had officially become “the vanguard of the people in their struggle to build a Socialist society”, words which were said to be so indistinguishable from the provisions of the 1936 Soviet Constitution. The article argued this was no accident; Nkrumah was dining with the Soviets and had become a “Black Stalin”. Western media and politicians were, therefore, up in arms against Nkrumah. Assassination attempt followed assassination attempt while the Western propaganda machine churned out mistruth after mistruth. Just how did Kwame Nkrumah who had been a champion of the politics of indifference and non-alignment end up so unaligned with the United States and the greater West?

The day is May 3, 1964 and The New York Times carries a scathing headline about a young African country, Ghana: Portrait of Nkrumah as Dictator. It gave a litany of cardinal sins that Kwame Nkrumah, the Ghanaian leader, had committed against democracy and civilization in general. Chief among these sins was that Nkrumah’s political party had officially become “the vanguard of the people in their struggle to build a Socialist society”, words which were said to be so indistinguishable from the provisions of the 1936 Soviet Constitution. The article argued this was no accident; Nkrumah was dining with the Soviets and had become a “Black Stalin”. Western media and politicians were, therefore, up in arms against Nkrumah. Assassination attempt followed assassination attempt while the Western propaganda machine churned out mistruth after mistruth. Just how did Kwame Nkrumah who had been a champion of the politics of indifference and non-alignment end up so unaligned with the United States and the greater West?

The Transient Convergence

Ghana was the first sub-Saharan nation to gain its independence and it carried the heavy crown all pioneers wear: the crown of precedent. It was the standard for other African countries and unsurprisingly, within ten years of gaining its independence, over 30 other countries had followed suit. Newly independent Africa was to become the ultimate battle front of the cold-war and thus major powers were taking notice. The scramble for ideological territory began with the Soviets on one side and the West on the other. America was especially anxious to take ideological control of Africa that it sent its Vice President, Richard Nixon, for Ghana’s independence celebrations. Richard Nixon would watch as Francis Nwia-Kofi Ngonoma (known as Kwame Nkrumah) took power. For a moment, the Western world’s interests, as embodied in the policies of containment, converged with the Pan-African nation-building agenda.

All the Visions, Dreams and Mistakes

David Rooney, in his work Kwame Nkrumah: Vision and Tragedy, said of the Ghanaian leader: he saw all the visions, dreamt all the dreams, and made all the mistakes. Nkrumah’s dreams and visions had taken him to the United States of America and later to the United Kingdom, where he studied and developed his guiding philosophy. Worried about the potential evil of Western education, he was to later admonish all colonial recipients of Western education, arguing they could potentially surrender their entire personalities to the theories they learnt in the West. He remained sober and one can even argue that he was able to use all he learnt for the greater benefit of his people. When he came back home, he had a clear guiding philosophy and a clear goal. He sought African unity and the liberation of his people. He envisioned a union of all African states and dreamt of freedom. In building the young nation of Ghana, he would adopt non-alignment which meant Ghana would engage with all countries despite their ideologies. Ghana would not pick any sides in the Cold war apart from its own side. Nkrumah told the American leader, Lyndon B. Johnson as much but America did not believe it. That Nkrumah went on to publish an uncharitable polemic of American policy (Neo-Colonialism) only made his standing worse in the eyes of the West. Former United States State Department official Robert Smith was to then reveal, “I think Nkrumah dropped the straw that broke the camel’s back, so to speak, in that he published a new book called Neo-Colonialism.”

The Fall of the Myth

At 6 a.m. on February 24th in 1966, one army leader, Colonel Kotoka announced to the world that, “The myth surrounding Nkrumah has been broken.” In retrospect, fewer mistruths have been told; Nkrumah’s mythical place in history as Pan-African giant had already been established. Kwame Nkrumah had been deposed by a coup while he was in China, on his way to Vietnam. The United States of America and the United Kingdom were in on the deal and declassified documents in Foreign Relations of the United States detail the countries’ involvement. The United States of America had prior information as to the coup, particularly the names of the coup plotters. A member of the National Security Staff, Robert Komer sent a congratulatory message to his President, Lyndon Johnson; and aid which had been tied up was organized for Ghana. It was a give and take.

For his part, Nkrumah had made a number of miscalculations in his quest to stay in power and see out his vision of a united Africa. He had become increasingly repressive, shutting down the democratic space in the country and attempting to consolidate his position as a President for life. The United States only exploited the discontent Kwame Nkrumah had fed and nurtured. Modern Africa has a lot to learn from Nkrumah’s dreams, vision and most importantly, his mistakes.